Dawn of a new era in Search: Balancing innovation, competition, and public good

Google search is in the news. Judge Amit Mehta ruled that Google search is a monopoly and is behaving in a manner that suppresses search competition with their distribution agreements. The debate on this has started, and various experts have presented pros and cons on the arguments, along with proposed remedies. We will analyze the extremely complex nature of this case and propose a novel remedy that goes into the heart of what we believe the Sherman Act is trying to achieve.

Before diving into the ruling, it’s important to note that while we (the authors) are not lawyers or experts on the Sherman Act, we have extensive experience in the tech industry and understand how technology and technology products are used.

And for those unfamiliar with Kagi, a brief disclaimer: We are a new participant in the search market, with Kagi Search, a search engine with a distinctive search experience that aligns the interests of users and the search provider. Additionally, we want to address a potential conflict of interest upfront: our proposal would benefit Kagi, but it would also create healthy, true and intense competition in the search space, including to Kagi, which aligns with our understanding of the Sherman Act’s intent.

What follows is written in good faith and with the utmost respect for the technology Google has developed and the talented individuals behind it. We acknowledge Google’s significant contributions: continuous investment in improving search technology, free access to search for billions of users, and innovations that have benefited the entire internet ecosystem. Our disagreement lies solely with the business model and its fit in today’s world. While the ad-based model for search has successfully delivered this service to the masses, the time has come to explore alternative business models that better align with user interests and emerging concepts of core data ownership. It is becoming increasingly evident that search results influenced by third-party interests, rather than consumer needs, are at best ‘for entertainment purposes’ and at worst harmful to consumers - an argument we will explore in more detail.

Our position is that the real harm to users does not stem from a lack of choice in search access, but rather from the lack of choice in search experiences themselves. Introducing a variety of search experiences would empower users to choose the one that best aligns with their needs, privacy concerns, and expectations, ultimately leading to a healthier and more competitive search market.

Let’s explore the main components of this case in more detail.

Overview of Google architecture

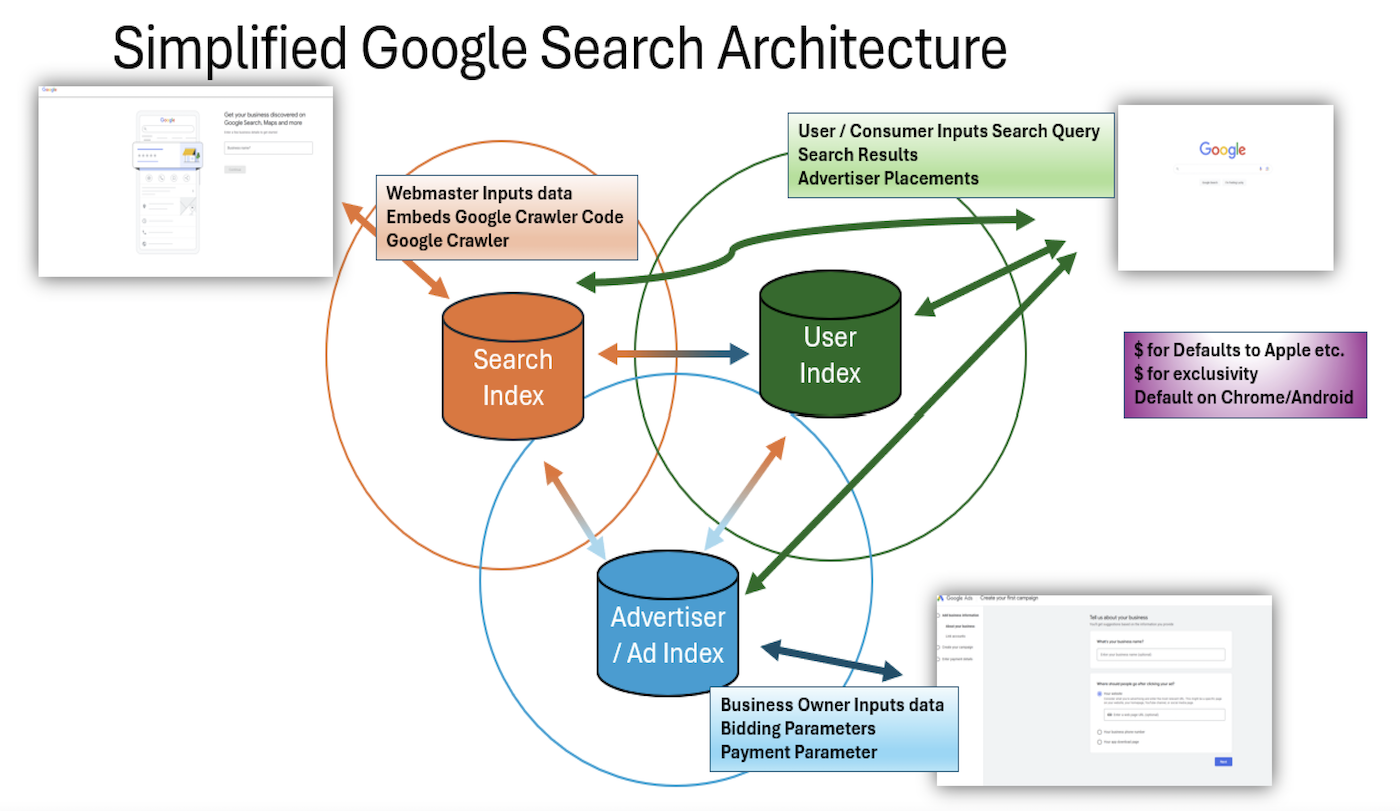

Here’s a simplified version of the Google architecture (click to enlarge):

Google has innovated on three core aspects of search:

- The Search Index

- The User Index

- The Advertiser Index

Let’s examine each in more detail.

The Search Index

Google has built a massive index of the internet that covers close to 100% of the accessible web. Over the years, Google has smartly invested not only in indexing the web but also in building intelligence to determine which “pages” have more relevant data for the user using algorithms.

These include: a) ranking webpages in terms of relevance (like PageRank™, which was patented but has since expired), b) speeding up crawling by embedding “free” code in websites to make them crawler-friendly, and c) ensuring self-validation of websites by asking webmasters to register their websites in the Google Search Console, verifying domain ownership. All these actions and reinforcements make the Google Index the best in the world and an indispensable resource for Google’s search business.

This makes the Search Index a very valuable asset that no other company has in its full complexity and size.

The User Index

The search engine bar/page is what the consumer or user sees when they start a search query. Google has innovated on the search bar/page by discerning search query intent, providing search query alternatives, location-based search queries, and search query presentation. Once the user enters a search query, Google uses the search index to present results based on what their algorithm anticipates the user wants to see, both for commercial and non-commercial queries. Additionally, the search page also shows ads, which is how Google monetizes their search business.

This is where Google pays companies like Apple over $20 billion a year for default placement in browsers. This default placement allows them to add almost all users on those platforms as Google search users, feeding the Search Index and the Advertising Index. Another valuable asset for Google here is the User Index, used to personalize ads to each user’s unique needs as determined by the algorithms governing the User Index. Google does not sell user data but monetizes it across all their platforms through ads. Independent sources say that Google has unique data on over 3 billion users worldwide.

The Advertiser Index

Google generates around $150 billion in search ad revenue (2022). This ad engine has its own team that drives innovation cycles. The Advertiser Index is the largest in the world for online advertising, covering over 90% of the advertisers globally. It is the repository of advertisers, their ads, and their payment plans, driven by complex reverse auction algorithms to place the right ad above the fold, below the fold, and to the right on a search results page. Users get to search for free because they are paying with their usage data for the ads they see and maybe click on.

With the massive volume of queries and ads served, even if users rarely click on an ad, the sheer volume is enough to generate the highly profitable revenue of USD $150 billion. The CTR (0.86%), CPC ($0.66), and CVR (1.91%) are the estimated stats for Google Ads. These seem small but are gigantic based on the number of users (over 90% of users come to Google), the number of queries (around 1.2 trillion a year), the number of advertisers (over 90% of the online market), and what advertisers are willing to pay for being on the Google platform.

It is estimated that Google generates over $50 per year per user in advertising revenue. Simple math: $150 billion revenue / 3 billion users = $50. Users in the US could easily generate 6 to 10 times the worldwide average, making this a very valuable cohort for Google.

Google’s self-feeding engine in action

As seen here, Google has built a self-feeding engine where users, advertisers, and webmasters (owners of websites) all willingly give their data, access, and money. This engine generates its own leadership/monopoly momentum where users of the platforms (users, advertisers, and webmasters) are willing partners in this scheme. Users get their search results free, but they must bear the burden of ads and misaligned incentives.

Advertisers get access to the world’s biggest online platform with the largest number of users, whom they can precisely target if they are willing to pay the highest prices for that benefit. Webmasters are eager as their websites are indexed on the world’s largest search index, giving users a chance to visit their websites, which they can monetize.

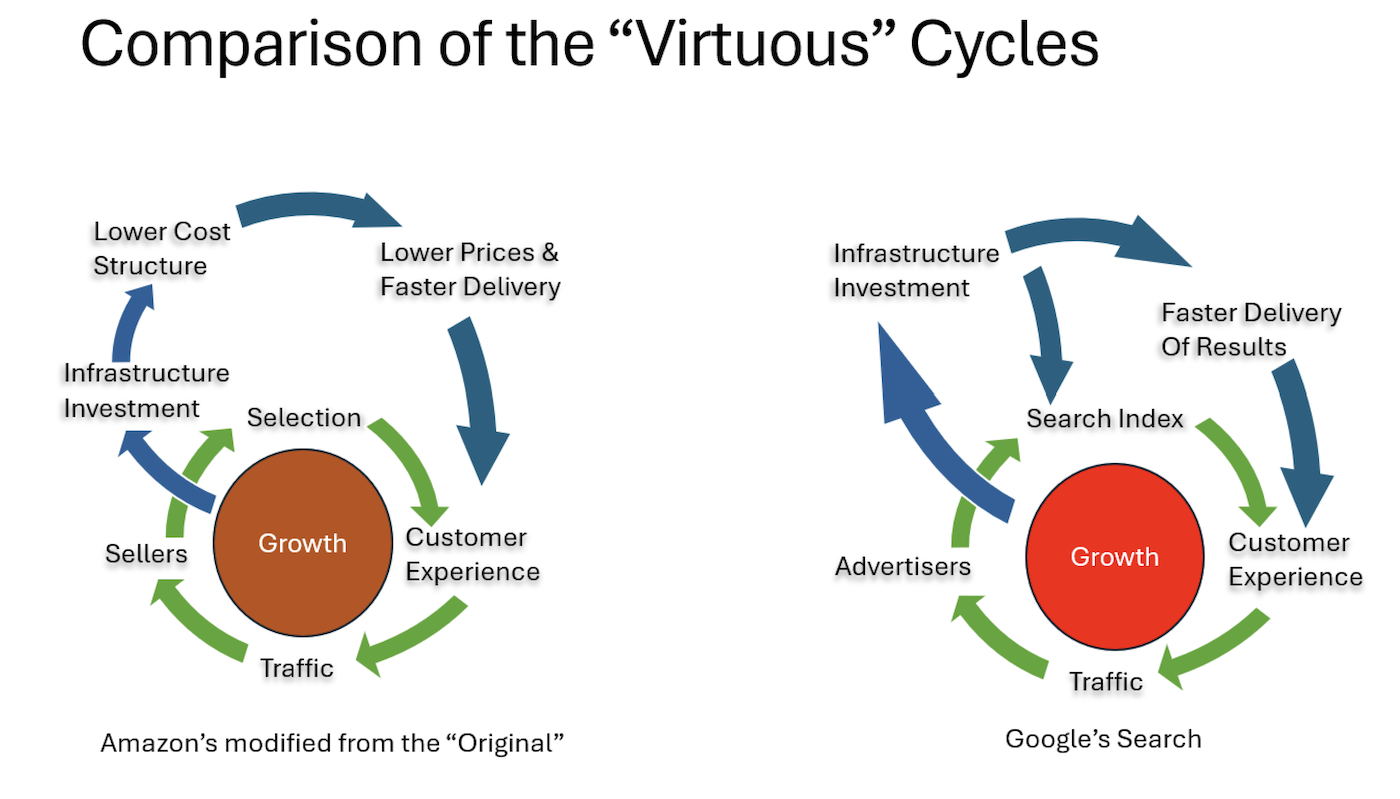

Google’s search economics and strategy is built on a flywheel very similar to the famous Amazon virtuous cycle:

The point here is that competitors can build competing cycles, but challenging a flywheel once it has gathered full momentum is very difficult. In Amazon’s case, they can be challenged by factors like price (which is non-zero), better choice, and user experience. However, with Google, the challenge is significantly harder because the nominal price is “zero,” while users pay in other currencies - personal data, attention, and changes in behavior. As a society, we are only beginning to recognize the importance of these currencies and the impact they have on our lives.

Now that we understand the architecture, the business strategy, and what goes into Google Search we can examine some key questions.

Is Google a monopoly?

This has already been decided by the judge and the answer is Yes.

Here is a simple table outlining a few key statistics:

| Category | |

|---|---|

| User query share | >90% |

| Advertisers on platform | >90% |

| Search Index coverage | >99% |

| User Index coverage | Over 3 billion |

The data shows that the powerful “Virtuous Cycle” flywheel loop driving the “free” search marketplace is overwhelmingly tilted toward Google. Google is a monopoly by market definition, having over 90% of the queries on their platform.

They have built this position over many years by pushing hard on multiple factors: early entry advantage to build the flywheel, consistent spending on innovation in all three areas, and doing everything to keep the advantage going. Even with Bing spending 5-10 billion USD a year, for the past two decades, it is not able to overcome the self-feeding juggernaut that Google is. Unless one is willing to break this self-feeding circle, there is no remediation or outside challenge that can overcome the Google monopoly.

Is Google preventing competitors from gaining a foothold and are competitors being harmed through default placement deals?

The answer is Yes and No.

It can be argued that default placements significantly contribute to maintaining Google’s market share, with Google reportedly paying companies like Apple over $20 billion for this privilege. Apple has stated that Bing does not match Google’s search result quality, and they are unwilling to compromise on user experience by offering subpar results.

A fair observer must acknowledge that being the default search engine within the Apple ecosystem holds substantial economic value - a value determined by fair market forces, with Google agreeing to pay that price. This may come as a surprise, but from our standpoint as a search market participant, this arrangement between Google and Apple is acceptable. (and interestingly what is more problematic is that Apple users cannot choose Kagi as their search engine at all, which consumers see as a hinderance - that said, this issue is beyond the scope of this article).

Even if the government mandates that Google cannot pay for this privilege, two things could happen:

- Apple loses $20 billion (Google’s windfall) but keeps Google to maintain consistency in the deeply entrenched user experience.

- Even if users are forced to contend with another choice, the user selection flow can be manipulated to favor Google, maintaining its dominant market share.

The result could still be the same - maybe Google’s market share goes down to 80% - is that still a monopoly?

Are users being harmed?

The answer is Yes.

This is harder to prove and more nuanced. The service is free to users, the search results are of the best quality among its advertising-driven peers and the results are presented in the blink of an eye. All of these might seem to be an advantage for users and Google.

Usually a relationship between a user and service provider is direct and the objectives of each are in alignment. In this case there are three parties involved – Google, the Advertiser and the user. Because of the three parties being involved, the objectives are misaligned. This misalignment arises because of the business model being used where Google and the Advertiser are aligned on pushing more ads to the users to generate more revenue while users would prefer to see fewer ads (or no ads) and information in their best interest. For example someone looking for ‘best headphones’ in an ad-based search engine will not get the actual best headphones, but sponsored results from companies which paid the most for the keyword ‘best headphones’. This is a profound mismatch in expectations.

There are four areas where users are being harmed (we acknowledge this is subjective and hard to prove empirically):

- Limited search results: Users do not get to see any other search results that will use a different set criterion for ranking and presentation and user choice. The user does not know if these are the best results for their query as in 99% of the cases the Google result as presented with ads and ads-based ranking is the only one they see.

- Ad saturation: Users are bombarded with ads. There are no significant number of search providers using a different business model, like subscription-based services, that present results without ad influence. Users see many ads and must navigate ad structures just to get to the results, which is very annoying and often intelligence-insulting.

- Privacy concerns: The ad-based model relies on user data, placing privacy in Google’s hands. Google “owns” the data (though they say users can manage their data on the platform, but people rarely do). These hyper-targeted ad structures can be easily manipulated algorithmically (hidden, untouched, and uncontrolled by the user), leading to unintended consequences in search result presentation. This can result in claims of user manipulation and bias enforcement.

- Misaligned incentives: The main problem with ad-based business model in search and the cause of factors above is the misalignment of incentives. The user and customer are different (customers are advertisers) and every business will try to do what is best for the customer. This will cause the user to be often presented with information and search experience that is not optimized for their needs.

Users might not care about the harm of being in the palms of advertisers and 3rd party interest (instead of their own) if the service is free. However, getting unbiased, correct information without influence from advertisers or other algorithms looking to manipulate users is undeniably critical for making the right decisions on information, purchases, politics, and scientific information.

If consumers are being harmed and no other competitive solutions are on the horizon to correct this, we must start looking at remedies that are lasting, easily enforceable, and easily cross-checked for compliance. If we do not apply these principles, the solution will fail or be more harmful to the users.

What are the right remedies?

The court has made its ruling, and discussions about remedies have ensued.

We will not delve into other remedies that have been already suggested (such as restricting default search agreements, providing access to clickstream and query data, or splitting AdWords, Android, YouTube, and Chrome from Google) because we believe they address the wrong outcome, basically trying to hurt Google and failing to pave the way for true innovation, more diverse competition and better outcomes for consumers. Readers are encouraged to explore the “References and further reading” section at the end of this article for more information on these approaches.

Instead, we should first step back and consider what is the fundamental problem that we are trying to solve?

The primary purpose of the Sherman Act is not to shield competitors from the success of legitimate businesses or to prevent those businesses from earning fair profits from consumers. Rather, it is to preserve a competitive marketplace that protects consumers from harm (see also Competition law and consumer protection, Kluwer Law International, pp. 291–293).

We’ve established that Google’s monopoly is rooted in its significant market share, which is sustained by critical assets under its unique control - the search index, the user index, and the advertiser index. Access to these essential assets is not available to any competitors.

The ad-based search experience, while highly successful, subtly exploits users in ways that are not immediately obvious, though evidence is steadily building.

We’ve heard from Kagi users that they cannot imagine going back to an ad-based search experience. They came to appreciate this straightforward incentive structure: if the search experience is not good, and they are not finding information they need, they can simply stop paying for the service, incentivizing the search provider to do better (see My Search Engine Is Perhaps My Favourite Tech Service and How Kagi finally let me lay Google Search to rest).

There is emerging academic research, such as the study Is Google Getting Worse? A Longitudinal Investigation of SEO Spam in Search Engines, that suggests a steady decline in search result quality across major ad-based search engines.

Google founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, predicted this would happen as far back as 1998, stating:

“The goals of the advertising business model do not always correspond to providing quality search to users.” … “We expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.”

And Google employees are saying this now themselves publicly:

But have you seen the internet recently? The top 5 results are usually just some garbage content farm that has buggy code from 2008 that’s been updated only for SEO and still doesn’t work.

It’s important to note that this decline does not indicate a deterioration in the quality of the Search Index itself. Rather, it reflects the choices made by search providers - in this case, Google Search - regarding what to show from that index to the consumer. Unfortunately, these choices seem to be increasingly aligned with the interests of advertisers rather than those of the consumer.

This has profound implications for the search landscape, as it suggests that other entities (government and privately own) could make different choices with the same Search Index - and create search experiences that better align with consumer interests.

And maybe most importantly, if we step back and ask ourselves what kind of society we want to live in, hardly anyone would say we want to consume critical information from sources that do not have our best interest in mind. Yet that is exactly how our current situation can be described.

Political scientist Ian Bremmer’s astute observation becomes particularly relevant in this context:

“The idea that we get our information as citizens through algorithms determined by the world’s largest advertising company is my definition of dystopia.”

This underscores the need to reassess our approach to search and information access in the digital age.

We think that any effective remedy should not attack Google’s business model or its remarkable ingenuity and execution. Instead, it should focus on access to core technologies within its flywheel that will foster more diverse competition. This approach would encourage the development of new solutions and business models in search, ultimately benefiting the consumer.

Of course, any remedy should pass the tests of:

- Is it long-lasting?

- Is it easily enforceable?

- Can it be easily verified?

There are three core technology aspects here: the Search Index, the User Index, and the Advertiser Index.

The User Index and the Advertiser Index are tied to the business model, and any remedy here will impact only the business (including payments for placements, etc.), with no actual benefit to the consumer. That leaves the Search Index.

The Search Index is the core engine that drives the search flow and generates results pertinent to the user. If we want different search products (the search page) to flourish and different business models for search products to flourish, we should consider separating the Search Index from the other two indexes and make the Search Index available to competitors. This will drive enormous innovation and free competitors to pursue different business models. The innovation on presenting results to users can center around different ranking criteria, different business models, and different user controls on the data they see.

Since search is a critical but essential resource for all users, the solution that can be considered is allowing fair access to the Search Index or take it a step further into known precedents, consider treating the Search Index as an “Essential Facility”.

The “Essential Facilities” Doctrine

The Essential Facilities Doctrine is an antitrust principle that requires the owner of an “essential” or “bottleneck” facility to provide competitors with access on reasonable terms. This doctrine has been applied across various industries, from railroads to news services and electrical utilities.

The doctrine traces its origins to the 1912 Supreme Court case United States v. Terminal Railroad Association, which addressed railroads controlling access to key bridges and facilities in St. Louis. This ruling laid the foundation for regulated access to the expansive railroad network in the U.S., even though it was primarily built by private companies.

Over the years, the doctrine has been applied in cases involving news services (Associated Press v. United States, 1945), electrical utilities (Otter Tail Power Co. v. United States, 1973), and more recently, cable distribution networks (Viamedia, Inc. v. Comcast Corp., 2021).

This doctrine ensures that critical infrastructure, such as railroad, power lines or communication infrastructure, built by private enterprises, serves the public good. It’s a principle that could also be applied to a unique bottleneck resource in the digital age - the Search Index.

Benefits of this approach

The Google Search Index is a unique and irreplaceable resource within the digital ecosystem. Allowing fair access to it or treating it as an essential facility could address the core issues identified in the US vs. Google case, aligning with the Sherman Act’s objective to promote innovation and genuine competition that benefits consumers.

The insurmountable challenge for any new search company to provide a novel search experience lies in the inability to build a Search Index that competes with Google, due to the enormous investment costs ($100B+ USD), technological barriers (web is not friendly to new crawlers), and time required (20+ years). It’s akin to expecting a new transportation company to build their own railroad infrastructure for the entire U.S. before even putting a train on the tracks.

Key components of the suggested approach include separating the index from the search product, allowing other companies to develop innovative search solutions using the same high-quality web index. Additionally, providing standardized, fair, and non-discriminatory programmatic access through well-defined application programming interfaces (APIs) is crucial, as Google’s Search Index currently remains the only major search index not easily accessible under commercially friendly terms.

Implementing a tiered pricing model would facilitate various levels of access, accommodating startups and established companies alike, enabling them to pay for access to the Search Index similarly to any other company. Establishing regulatory oversight through a dedicated body would ensure fair access and compliance. These measures would foster a more competitive and innovative search ecosystem, benefiting consumers and the broader market.

This would bring about several significant benefits:

- Increased competition: Lowering barriers to entry would encourage the development of new, specialized search engines and applications.

- Alternative business models: This approach would enable the creation of paid, private, and free public search options, offering consumers more choice and aligning with their varied needs and preferences.

- Improved privacy options: By facilitating search products that don’t rely on data collection for advertising, users would have greater control over their privacy.

- Enhanced search quality: Increased competition could lead to improvements in algorithms and overall user experience, benefiting consumers.

- Preservation of search as a public good: Ensuring broad access to high-quality search capabilities would help maintain search as a vital resource for everyone.

- Economic growth: Opening up the search index could drive the creation of new businesses and services built on search capabilities, contributing to overall economic growth.

- Enabling a public search engine: Last but not least, when considering how we access information as citizens in a modern society, it is crucial to recognize information access as a fundamental human right. The traditional role that public libraries played for centuries in informing citizens is no longer sufficient in the digital age. A public search engine could ensure non-discriminatory access to information, funded by taxpayer money, serving the best interests of all citizens. Imagine it as your local public library on steroids.

Addressing potential challenges

Our proposal raises important questions and potential challenges, including:

- Impact on innovation incentives

- Technical feasibility

- International coordination

- Fair compensation

- Unintended consequences

While significant, these challenges are not insurmountable. Open dialogue and expertise from various sectors can lead to workable solutions.

A Path Forward

Judge Mehta’s ruling has opened a window for meaningful reform in the search market. By opening access to the dominant search index or treating it as an essential facility, we have the opportunity to foster a more open and competitive search ecosystem that better serves users’ needs.

As we move forward, it’s crucial to remember that the future of search will impact how we access information, make decisions, and understand the world. This future should be shaped through collaborative efforts considering all stakeholders’ needs, especially end-users.

To realize the benefits of this proposal, we must also address the broader ecosystem, including promoting more choices in web browsers and empowering users to select search engines that best meet their needs and values.

Policymakers, industry leaders, and the public should join this crucial conversation. Together, we can work towards a future where search technology is harnessed for the greatest public good, fostering innovation, respecting privacy, and ensuring equitable access to the world’s information - all while prioritizing the needs and rights of consumers.

References and further reading

- US. v. Google Judge Mehta ruling (PDF)

- A Critical Analysis of the Google Search Antitrust Decision (International Center for Law & Economics)

- The DOJ’s Google Search Case – What Next? (Tech Policy Press)

- “Google is a Monopolist” – Wrong and Right Ways to Think About Remedies (Tech Policy Press)

- An analysis of potential remedies to address Google’s search monopoly (Consumer Reports)

- Friendly Google and Enemy Remedies (Stratechery)

Published by Raghu Murthi and Vladimir Prelovac on August 29, 2024. Authors would like to thank Megan Gray for prior discussions on this subject.